Despite common ancestry in English rugby football, Canadian football has long stood apart from its American cousin. The Canadian Football League (CFL) plays on a field that is 110 yards long, with two 20-yard end zones, and 65 yards wide, compared to the NFL’s 100-yard field with 10-yard end zones and a width of 53⅓ yards. Bigger country, bigger football field, you might say. These differences at the pro level exist alongside three downs instead of four, and they cascade down into university and high school play as well.

Date

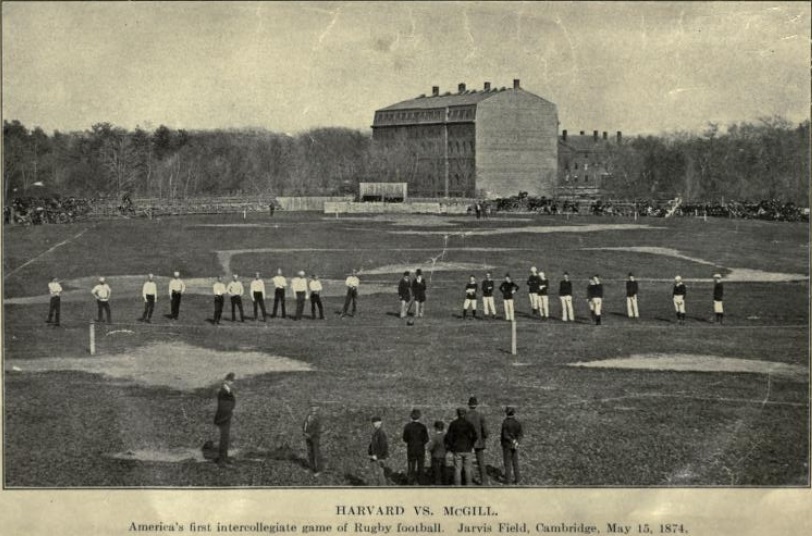

Taken on 15 May 1874

Source

From the book “Football – The American Intercollegiate Game”, written by Parke H. Davis in 1911 and no longer in copyright

Under Commissioner Stewart Johnston, a Queen’s University graduate who took office in April 2025, the CFL has proposed and begun to phase in a package of changes that will move aspects of the game toward NFL norms. In 2027, the league will move the goal posts to the end line, shorten the field from 110 to 100 yards, and reducing end zones from 20 to 15 yards. These details were announced by the league and summarized in national coverage.

Fan reaction has been mixed. One organized response is a petition by CFL fans calling for a two-week blackout to delay the implementation of the changes, on the grounds that they erode the distinctive character of Canadian football. The petition and the surrounding discussion make plain that identity and tradition matter in sport, and that any shift toward alignment with the American game will be scrutinized closely by the league’s core audience. Today, the Globe and Mail, Canada’s national paper of record, denounced the pronounced rule changes in nationalistic, quasi-religious terms as breaking a “covenant”. That piece in the Globe prompted me to write this blog post.

I strongly support the proposed convergence of rules. The CFL commissioner is doing the right think. Harmonization reduces transaction costs for broadcasters, equipment suppliers, analytics firms (think of Moneyball but in age of AI), and sponsors who operate across the Canada–United States market. Players benefit from fewer adjustment frictions when moving between leagues or training environments. On a broader level, harmonization deepens the interconnection between Canadian and United States football economies in such areas as media rights, merchandising, talent mobility, and joint ventures in youth development, and it thereby enhances bilateral returns from cross-border synergies. These are exactly the sorts of effects one expects when regulatory regimes become more compatible.

The economists’ gravity model of trade helps explain why this logic travels beyond sport. The model holds that trade between two economies rises with their economic size and falls with distance, where distance includes not only geography but also regulatory difference. Canada trades far more with the United States than with distant partners because the United States is both very large and very close in every relevant sense, including legal and regulatory familiarity. A contemporary illustration of why gravity models matter in thinking about regulation is the United Kingdom’s experience after Brexit. The Brexiteers wanted UK rules to diverge from European ones because divergence felt good, at least for them. However, they should have looked at a map before deciding whether regulatory divergence from Europe is the right policy– fact is, the UK is in Europe. Even small increases in regulatory distance from the European Union created non-tariff barriers, compliance costs, and uncertainty that weighed on trade, despite the minimal geographic distance. The lesson is straightforward. When regulatory distance grows, exchange tends to fall, even where countries sit side by side. The UK should, almost always, harmonize regulations with the EU, unless there is a really compelling reason for divergence. Similarly, Canada should, almost always, harmonize regulations with the US, unless there is a really compelling reason for divergence.

History offers a practical reminder of what happens when standards diverge from infrastructure. During the CFL’s United States expansion in the mid-1990s, several American venues struggled to accommodate a full Canadian field. In Memphis, for example, attempts to fit the larger geometry into the Liberty Bowl produced irregular, truncated end zones that were reported to be as shallow as seven to nine yards at certain points, an awkward solution that undercut the on-field spectacle. I distinctly recall that being discussed at the time, although until today I had forgotten about the problems involved in squeezing a CFL playing field into a US stadium. Lack of rule harmonization was not the main reason CFL expansion into the US failed, but it was a factor.

None of this is an argument for indiscriminate alignment in every last area of life. There remain moral, cultural, and constitutional domains where distinct Canadian standards are appropriate just as there is a case for the UK retaining Imperial units of measurement in a few spheres of life that aren’t that important to visting Europeans. Nobody wants Canada to start using the electric chair because the US does. I kinda like that my local fruit and veg trader here in England can now sell in pounds of weight as well as pounds of money, although I would trade that for the right to live in the south of France near the Med. Nor would I deny that there is some value in trade diversification efforts: Canada has periodically explored trade diversification strategies, from the Third Option in the 1970s to more recent efforts. However, the structural forces described by the gravity model will keep the United States as Canada’s principal economic partner for the foreseeable future. In that context, targeted harmonization of rules is less a surrender of sovereignty than a way to sustain it.

If you don’t want Canada to become the fifty-first state, you need to make Canada as rich as possible. The best route to preserving meaningful independence is a strong economy, and building such strength involves deeper trade with the United States and regulatory compatibility that enables it. To have a strong country, army, navy and so forth, you need a rich economy to act as its tax base. To get to that rich economy, you sometimes need to adopt rules and institutions from the hegemonic power. Paradoxically, building a richer and more sovereign Canada involves adopting US rules.

Leave a comment