When Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney framed his new infrastructure and resource agenda as a “nation-building” project, he tapped into an old Canadian ambition: escape velocity from the gravitational pull of the U.S. market. The motivation for this sudden interest in trade diversification is Donald Trump’s stated intention to use tariffs as leverage to force Canada to become the fifty-first state. That threat has sharpened Ottawa’s incentive to diversify exports in a way that successive Canadian governments, dating back at least to the Ottawa Economic Conference of 1931, have aspired to but consistently failed to achieve.

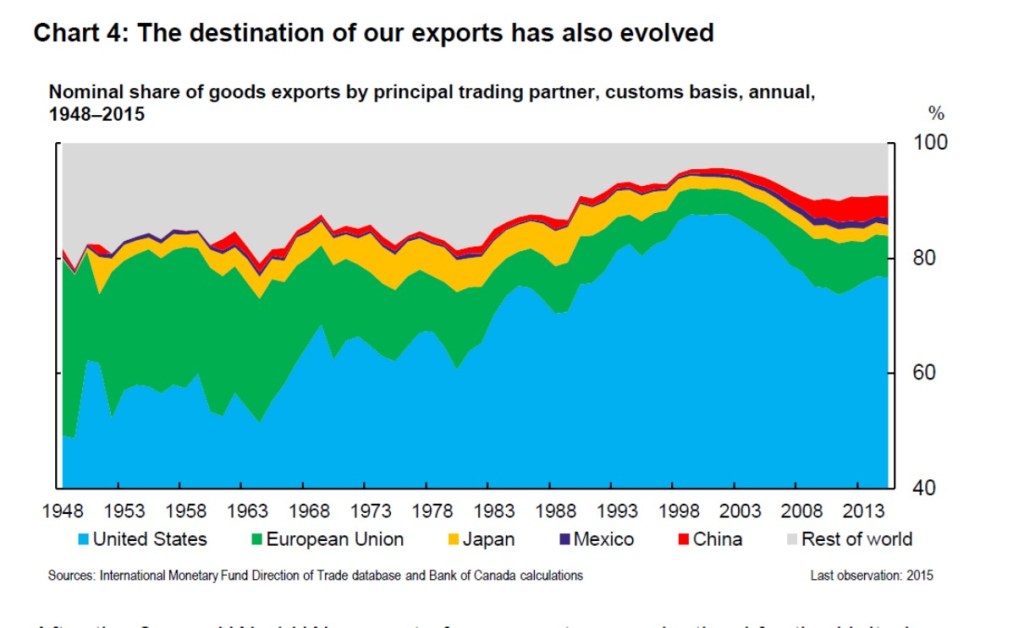

Image source: 2016 presentation by Lawrence Schembri of the Bank of Canada to the AIMS think tank in Halifax.

This historic pattern has been remarkably stable. The history of Canada’s efforts to divert trade away from the United States is a boulevard of broken dreams. Whether Canada pursued Commonwealth preferences (the sentimental favourite of the political right in Canada), Pierre Trudeau’s “Third Option” in the 1970s (which envisioned closer trade ties with the social-democratic countries of the EEC), the Asia pivot of the 1990s (which involve Team Canada trade missions in which a plane load of politicians and businessmen flew on a glorified sales mission), the structural fact remained: the U.S. absorbed the overwhelming majority of Canadian exports. Geography, cultural similarity, scale, integrated supply chains, and risk-minimizing behaviour by firms kept the share stubbornly high. The Team Canada trade missions of the late 1990s appear to have had nearly zero impact on Canada’s international trade, as academic researchers have statistically demonstrated. The relative importance of Asian export markets to Canada did increase after 2000, that appears to have been driven entirely by economic growth in Asia rather than Canadian government policy.

The question right now is whether the latest tranche of so-called fast-tracked projects, which involve such commodities as so-called critical minerals, LNG, graphite, and electrons flowing down wires, can meaningfully reduce Canada’s degree of export dependence on the United States. The real question is not whether these projects are “nation-building” in an abstract national-identity sense, but whether they actually shift the geography of Canadian exports. On that metric, only one of these projects really matters, for reasons I will explain below.

I decided to invest a bit of time in trying to figure out which of the newly announced projects is likely to do the most to change the overall headline figure. So I looked at some of the documents related to four projects with clear export potential—Northcliff Resource’s (TSX:NCF) Sisson mine (tungsten/molybdenum), Crawford (nickel), Ksi Lisims (LNG), and NMG Phase 2 (graphite) and then tried to estimate how many dollars of exports each of them would likely generate in 2030 and 2035, if all of the plans come to fruition without delays. I know that’s a highly charitable assumption, given we are talking about Canada. For fun, I also tried to estimate how many full-time jobs each project would create since there is a lot of concern in Canada right now about the country’s high unemployment rate, the outflow of talent to the US, and falling fertility rates.

| Project | Estimate of annual exports (US$) | Exports to US | Exports to RoW | Share of project sales that are exports | Share of exports going to US | Approx. FTE operations (2030 & 2035) |

| Sisson Mine (NB – tungsten/moly) | $0.31 bn | 190m | 120m | 90% | 60% | 300 FTE |

| Crawford Nickel Ontario | $560m | $340m | $220m | 70% | 60% | 1,000 FTE works in the greater Timmins area |

| Ksi Lisims LNG (BC) | $6.86 b | $0 bn | $6.86 b | 100% | 0% | 700 FTE (operations) |

| NMG Phase-2 – Matawinie + Bécancour (QC) | 180m | 110m | 70m | 85% | 60% | 350 FTE (mine + battery plant) |

| Iqaluit hydro (NU) | $0 (no exports) | 0 | 0 | 0% | – | 20 FTE, likely seasonal |

| North Coast Transmission Line (BC) | $0 (no direct commodity exports) | 0 | 0 | 0% | – | order of 100–150 FTE (grid ops & maintenance) |

I could show you my rough work, but I estimate the total annual export value in 2035 or US$7.9billion or C$10.3billion. Of these exports, I estimate US$7.3 billion or C$9.5billion, will go to countries other than the US. As well, it seems that for most of these projects, with the obvious exception of the Iqaluit summertime hydroelectric project, virtually none of the commodities produced will be for the domestic Canadian market.

The arithmetic is unambiguous: roughly 87% of incremental export value from Thursday’s announcement is expected to come from just one of the new projects announced by Carney, that’s the LNG project. The LNG from this facility will overwhelmingly go to Asia, where energy is much more expensive than in North America and there is a desperate desire to stop using Russian energy. The export revenue and export diversification potential of the other projects is pocket change. The critical minerals and processed graphite are supposed to feed into the North American EV supply chain. (During the Biden era, Canada hoped that it would be part of emerging North American value chain. That’s why it put massive tariffs on Chinese EVs. The vision of the future that animated the Canadian government was of Canadians driving around in EV Chevrolets and Fords that were manufactured in the Great Lakes region of North America).

How Much Will Any of This Contribute to Diversification?

If it is built on time and on scale, the LNG project could have small but positive impact on the variable that the Carney government claims it wants to move downwards, the percentage of Canadian exports that go to the US. In 2023, Canada’s total exports of goods and services were about 600 billion USD. Ksi Lisims is designed for 12 mtpa of LNG, supplied by roughly 1.7–2.0 bcf/d of gas, with first shiploads leaving Canada in late 2029. In 2030, it will start earning foreign exchange for Canada. Now if we assume, for the sake of simplicity, that the price of a bcf of LNG will be the same in 2030 as it is today and that Canada’s overall exports will from between now and 2030 will increase at the historically expected pace, a fully operational Ksi Lisims LNG facility could account for roughly 0.7–0.8% of the value Canada’s total exports in the calendar year 2030. That’s not nothing.

When I look at the few concrete steps the Carney government has taken to diversify Canada’s trade away from the US, I’m convinced they are mostly symbolic. In that sense, they are strikingly similar to the Global Britain rhetoric we heard in the UK for a few years after Brexit. The UK spoke about striking ambitious trade deals with distant countries but was unwilling to do much in that area, in large part because of the domestic political costs of some of the trade deals proposed. I’m also concerned that policymakers are allocating an increasingly scarce resource, attention, to issue that have no export potential. The fact that a really important LNG project sits on the same list as some tiny projects suggests that the list-makers aren’t prioritizing.