For years, I have been thinking about the likely impact of AI on labour markets. In fact, I taught a career strategy class for first-year university students that introduced them to the scholarly debates about the automation of different types of cognitive tasks and then got them thinking about how they should adapt their career strategies to AI. I explained that AI was going to eliminate a few jobs entirely and would replace human input in parts of jobs. (Many jobs involve bundles of different tasks). The students usually ended up writing that they needed to use their time at university to develop skills that are complementary to AI. My point is that I’ve spent a fair bit of time thinking about how AI will impact different labour markets.

One of the most consequential but still under-examined implications of artificial intelligence is its likely impact on the boundaries of firms. Until recently, I wasn’t thinking about how AI is going to change the case for vertical integration. In this blog post, I’m going to try to use business history to think about these issues.

As Ronald Coase observed in his 1937 paper on “The Theory of the Firm”, firms arise to internalize those activities that are too costly to handle through contracts and arm’s-length exchange. Coase was trying to answer a deceptively simple question: if markets are so great, why do firms exist at all in a market economy? If markets are so wonderful as efficient allocators of resources, what justifies the creation of hierarchical structures that internalize production? Each large firm is an island in command economy hierarchy in a sea of market forces. Coase’s answer lay in the concept of transaction costs, which the costs associated with using the market to coordinate activity. These include the costs of finding suppliers, negotiating and enforcing contracts, and, crucially, the costs of dealing with opportunistic behaviour. When these market-based costs exceed the costs of managing an activity internally, through direction, authority, and monitoring, that changes the Make or Buy decision of that company. This logic underpins the concept of vertical integration, where a firm extends its boundary to include upstream suppliers or downstream distributors to avoid the frictions of market transactions. The make-or-buy decision thus turns on a comparative assessment of transaction costs inside the firm versus those incurred in the open market.

A classic illustration of this logic comes from the case of General Motors and Auto Fisher Body, which has been extensively discussed in the literature on transaction cost economics and by my fellow business historians (see here, here, and here). Initially, GM sourced automobile bodies from Fisher Body via a long-term contract. However, as demand for comfy “closed-body” cars surged in the 1920s, GM became increasingly dependent on Fisher. Fisher got the upper hand and exploited its power. Fisher, in turn, had little incentive to invest in production facilities that were close to GM’s assembly lines, and there were allegations that they exploited GM’s dependence by pricing opportunistically. According to the prevailing interpretation of this episode, Fisher Auto Body’s managers were only adhering the letter not the spirit of their contract with GM. According to the transaction cost interpretation, this created a classic case of asset specificity: Fisher had made investments tailored to GM’s needs, and GM was exposed to hold-up risk. In response, GM chose to vertically integrate by acquiring Fisher Body, thereby eliminating the need for ongoing contract renegotiation and securing control over a critical input. While some of my fellow business historians have questioned the details of this narrative, the case remains a widely used teachable example of how transaction costs, particularly those arising from relationship-specific investments, can drive firms toward integration by undermining the rationale for using the market.

My strong impression is that AI, especially when coupled with automation, predictive analytics, and large-scale data infrastructures, is reshaping each of the three main categories of transaction costs: search and information costs, bargaining and contracting costs, and monitoring and enforcement costs. Each of these shifts the relative attractiveness of market-based coordination versus managerial hierarchy, and each of them is already playing out in real firms right now.

My thinking about all of these issues has been influenced by Thierry Warin, a Montreal-based economist whose recent California Management Review piece, From Coase to AI Agents (2025), got me thinking about this issue. Warin suggests that the rise of AI agents changes not just the microeconomics of transaction costs but the architecture of organizational coordination itself. He builds on Coase but extends their insights into a world populated by autonomous agents, predictive models, and generative tools. Warin’s suggest to me that while AI can certainly lower the costs of using managerial hierarchies (it makes it easier of managers to monitor their subordinates), it is almost certainly going to lower the transaction costs involved in using the market to the greater extent. As such, it likely to shift, in many industries, people from reliance on coordination using managerial hierarchies to using coordination by the market. So we will see fewer cases of companies acquiring their suppliers, as GM did with Fisher Auto Body long ago. In fact, AI may cause the vertical disintegration of firms, accelerating a trend we saw in the late 20th century, when then great vertically integrated firms constructed in the first part of the twentieth century were replaced by coordination by the market.

Here’s what I have taken from the new work on AI and the theory of the firm. AI significantly reduces search and information costs, even more than the was the case with Google searches. Intelligent agents, algorithmic procurement systems, and even natural language interfaces now make it cheaper to identify suppliers, assess their offerings, and match capabilities. Pre-AI and, especially, pre-World Wide Web, the difficulty of finding a reliable vendor with the right specialization created a very strong commercial rationale for integrating the function in-house. Now, many of those frictions are collapsing, along with the case for vertical integration.

AI can also assist in bargaining and contracting by writing very good, watertight totally “complete” contracts, evaluating risks, and even simulating negotiation outcomes. Smart, self-enforcing contracting frameworks, potentially supported by blockchain infrastructure, embed enforcement directly into digital exchanges, can reducing ex-post haggling and the costs of opportunism (think of Fisher Auto Body). Lastly, the cost of monitoring third-party performance, traditionally a major argument for internalization, is falling. Thanks to the internet of Things, you can monitor what a distant supplier is doing in real time and at lower cost than was the case thirty years ago. Thanks to AI, you can interpret all of that data without hiring lots of human compliance and monitoring people. Real-time analytics, machine vision (you don’t need a human to count how many units come of the assembly line), and anomaly detection (an AI agent can inspect the quality of the auto bodies that today’s Fisher Auto Body is sending to today’s Alfred P. Sloan) will let upstream firms oversee quality and compliance without being physically present or organizationally intertwined.

This shift in the transaction cost landscape might suggest a simple conclusion: AI favours vertical disintegration everywhere and always. I suppose the actual effects of AI are context-dependent, and the classic Coasian trade-offs don’t disappear. In some industries, new technological capabilities reduce some transaction costs but increase others. For example, AI systems are often cognitively opaque. (Do I really understand the AI system that allowed me to find a great deal on my hotel for the Academy of Management?). A company may outsource an analytics task to an external AI provider, but understanding how the system arrived at a decision and ensuring that it didn’t do something reputationally or ethically risky (here’s where the business ethics professor comes in) may be more difficult than managing a transparent internal process.

This gives rise to a more nuanced map of trade-offs. In some domains, especially those involving modular, standardized, and relatively routine tasks (making auto bodies for Alfred P. Sloan), AI will promote market-based governance and strengthen the case for vertical disintegration. In others, particularly where the decisions are ethically or legally fraught, AI may actually reinforce the case for vertical integration. The table below summarizes these contextual trade-offs.

In effect, AI reduces the traditional cost penalties of outsourcing, but it also introduces new strategic uncertainties. As a result, we should expect to see increasing divergence across industries and functions in how firms draw their boundaries. This is already visible in early-stage evidence. For example, some companies are disaggregating their analytics and marketing functions, relying on external AI vendors with scalable expertise. I hope those firms know what it going on within the AI products they are buying. Meanwhile, Tesla has reintegrated key parts of its supply chain, including battery production and chip design. I bet they are doing so to remain complaint with the law.

In some industries, like precision medicine, defence, or autonomous vehicles, require complex coordination between proprietary hardware, sensitive data, and domain-specific machine learning. In those cases, control over process and data becomes a source of value, which means that vertical integration offers benefits in the age of AI that weren’t there before.

| Sector | Likely Impact of AI Firm Boundaries | Rationale |

| Digital marketing, logistics/trucking | Disintegration | High modularity, low IP sensitivity, strong market tools |

| Healthcare, defence | More vertical Integration | Regulatory complexity, liability, ethical accountability |

| AI infrastructure providers | Integration | Data, IP, and learning compounding advantages |

To put this all in perspective, it helps to bring research from my home field of business history into play and discuss how firm boundaries have evolved in response to past technological changes that shifted the cost of moving information. These new technologies, the telegraph, the fax machine, etc all changed transactions in different periods, and thus the case for using vertical integration in the face of a difficult Make or Buy decision.

Let’s draw on the work of Alfred Chandler, a historian of business organization who, in the 1970s and 1980s, laid the groundwork for our understanding of vertical integration in the industrial age. To people outside of the business history fraternity, Chandler is best known for The Visible Hand (1977), where he argued that the rise of large, vertically integrated firms in decades around 1900 was driven by their ability to coordinate better than the invisible hand of the market. His argument, which was strongly influenced by Ronald Coase’s theory of the firm, was that as railroads, the telegraph, and the telephone lowered internal communication costs, it became more efficient to organize production hierarchically and within big firms. The visible hand of management replaced the invisible hand of the market because of technology. If the AI is likely to promote vertical disintegration in many industries today, the telegraph had the opposite effect in the age of John D. Rockefeller and Alfred P. Sloan.

Chandler’s story is one of integration enabled by coordination. He documented how firms like DuPont, General Motors, and Standard Oil created internal hierarchies to manage flows of materials, information, and decision-making in ways that captured economies of scale and scope. The availability of the telegraph and the typewriter made real-time internal coordination feasible. Centralized administrative systems, bolstered by accounting innovations, allowed firms to replicate their managerial processes across divisions. The relative cost of internal governance dropped below the cost of external contracting and vertical integration became the rational response.

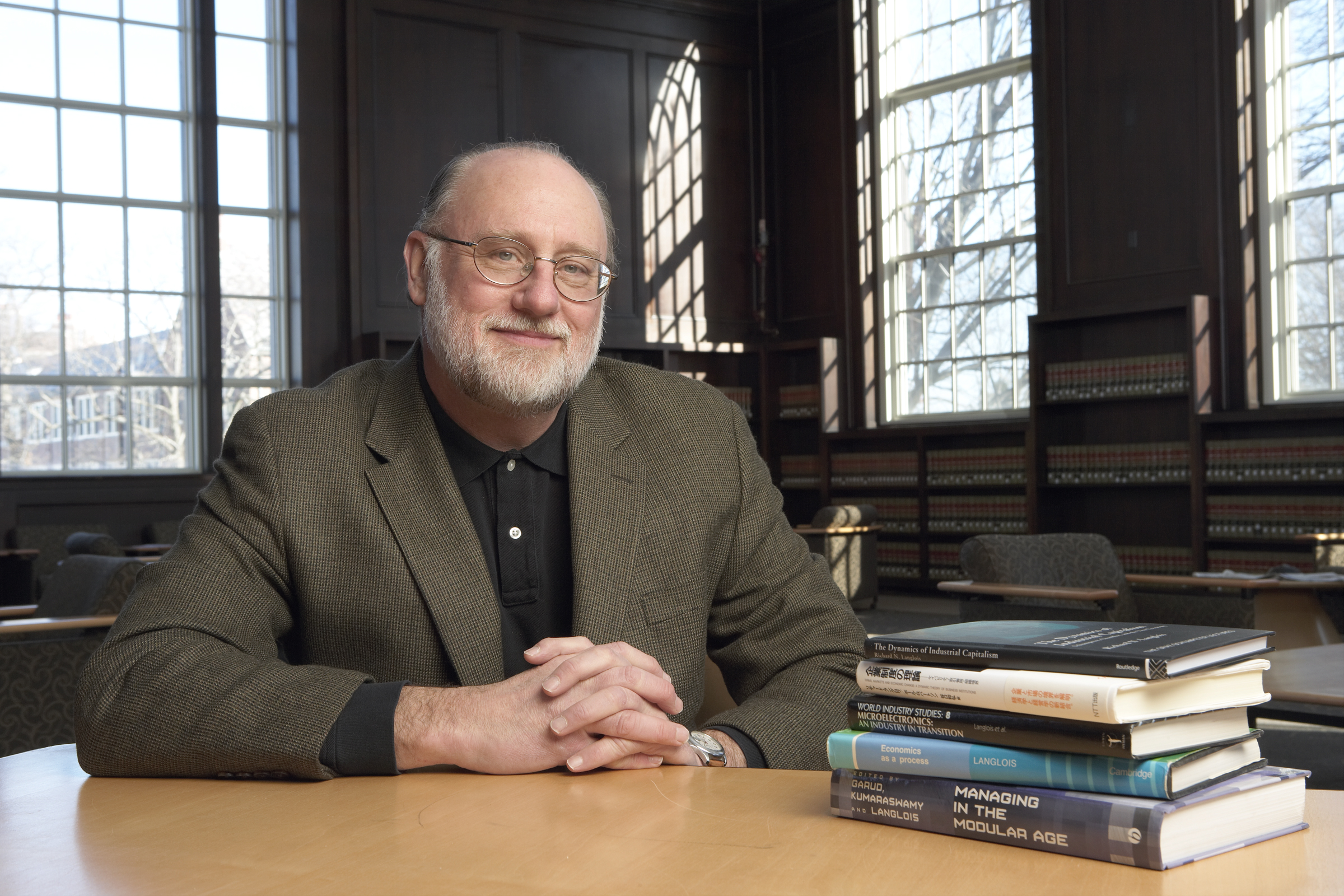

Chandler developed his ideas in the 1960s and 1970s. Almost immediately after he published his landmark book, new communications technologies began to reduce the costs of using markets, which then helped to produce a wave of vertical disintegration. A brilliant economist and historian of technology, Langlois advanced what he called the “vanishing hand” thesis, deliberately inverting Chandler’s title. In a series of papers published around 2000 and then a book that I recently and glowingly reviewed in the journal Business History, Langlois argued that Chandlerian integration was historically contingent. It was a response to immature market institutions and underdeveloped communication infrastructure. Once information technology advanced, market coordination became viable again, and firms began to shed internal functions in favour of modular, contract-based production. Langlois saw the return of the invisible hand.

Chandler saw the rise of vertically integrated firms and managerial hierarchies as a functional response to the challenges of industrial coordination in the early twentieth century. Big firms emerged, in his telling, because they could do what markets couldn’t: coordinate complex production and distribution systems more efficiently. Langlois, writing decades later, picks up the pen where Chandler put it down and then continues the story. His “vanishing hand” theory argues that by the late twentieth century, those same large, bureaucratic firms, which were oligopolistic, integration-heavy, and middle-manager-laden, had outlived their usefulness in most sectors. Once the economy moved through the transitional phase Chandler had chronicled, the visible hand of management became less necessary. Technological progress, especially in computing and communications, lowered the cost of outsourcing and made decentralized coordination viable again. As a result, market selection started penalizing firms that clung to the old integrated model.

Where Chandler saw integration as a triumph of managerial capacity over market chaos, Langlois saw it as a workaround: a temporary fix until markets and modularity caught up. Seen from a Langloisian perspective (I just made the adjective up), improvements in the market’s ability to handle complexity, which are driven by IT, digital standards, and now AI, restore the advantages of specialization and exchange.

Take-away lessons

My reading of history suggests to me that AI is going to have a big impact on firm boundaries (I’m very confident of that), and that it will, on net, encourage vertical disintegration in most industries (I have moderately high confidence in this history-informed prediction).

Right, so what are the implications of these two history-informed claims about the future for investors? By investors, I mean people who aren’t passive investors in index funds but who are in the foolishly/risky game of picking stocks. If AI is indeed going to analogous in its effects on levels of vertical integration to Morse’s electric telegraph, Malcoln MacLean’s container ship, and World Wide Web, then active investors should be thinking less about which firms can own the full value chain and more about which ones are best positioned to orchestrate, specialize, or intermediate. The big opportunity lies not in backing vertically integrated giants, but in identifying firms that sit at key nodal points in increasingly disaggregated value chains. This includes infrastructure providers with privileged access to training data or cheap computing power (e.g., foundation model specialists), platform firms that coordinate ecosystems rather than build everything themselves, and hyper-focused specialists that can carve out high-margin niches in the long tail of modularized functions. Investors should also be attentive to companies with architectural leverage: those that define the protocols, interfaces, and workflows that others plug into.

I never give investment advice on my blog. However, if I were to make a suggestion for short sellers based on my reading of history, it would be to would be target firms whose business models remain over-invested in vertical integration at a time when AI-enabled disintegration becomes the lower-cost, higher-flexibility equilibrium. These are companies that double down on doing everything in-house (manufacturing, analytics, logistics, customer service) even as AI makes it increasingly efficient (and strategically necessary) to specialize, outsource, or orchestrate ecosystems instead. Chandlerian-style firms that depend on tightly coupled hierarchies and rigid internal workflows may find themselves bloated, slow to adapt, and burdened by fixed costs in an economy that increasingly rewards nimbleness and interoperability. If they fail to unbundle or pivot, their margins erode and their strategic relevance declines. I’m thinking of Intel here.

The most promising short candidates would be firms that (a) operate in sectors where vertical disintegration is becoming increasingly feasible due to AI, such logistics, IT services, legal or back-office operations and then (b) persist with high internal headcount, capital-intensive infrastructure, or proprietary tech stacks that do not interface well with emerging AI ecosystems. I’m not saying that vertical integration would be maladaptive in all sectors. In domains where AI introduces new opacity, liability, or tightly coupled learning loops, such as like national defence (think of NATO’s new 5% target), biotech, or autonomous systems, vertical integration may remain rational.

Let turn now from the implications for investors to the societal implications. So what is this going to mean for the non-stakeholder shareholders of firms? For workers, local communities, governments, and the natural environment?

Gerald Davis’s The Vanishing American Corporation (2016) tells the story of how the large, vertically integrated corporation, which was the dominant organizational form in American economic life at the time Chandler wrote his book, has steadily eroded since about 1980. He attributes this shift to changes in technology, finance, and ideology that made it increasingly feasible and desirable for firms to disaggregate. His account is congruent to that of Langlois, except that Davis is more interested in the implications of this change for workers, for Joe Sixpack in places like Michigan. (Davis works at a university in Michigan!). In his account, as supply chains became global, digital technologies reduced coordination costs, and capital markets demanded flexibility and short-term performance, firms began to outsource everything from manufacturing to HR to R&D. The core transaction-cost logic here mirrors Richard Langlois’s “vanishing hand” thesis: improvements in market-supporting institutions and technologies enabled tasks that once had to be done internally to be done more efficiently through the market. Davis shows how the vertically integrated firm, which once offered stable lifetime employment to male breadwinners, predictable career ladders, and a broad social compact, gave way to leaner, more modular organizations and thus ultimately, to platform-based firms with minimal internal labour forces. The social implications, in Davis’s view, are stark: the decline of the traditional corporation has undermined job security, frayed the link between firms and communities, and contributed to rising inequality and precarity. If I were Davis, I would predict that AI will deliver even more of the same.